The Price of Being Strong: Risks to the Mental Health of Athletes

Although the London Games are over, the rush of the Olympic “spirit” still lingers in the air. It’s always inspiring to watch the world come together to celebrate athletes who’ve managed to excel, push their bodies to their maximum potential, and compete at the highest level. The Olympic motto spells our expectations out most simply, “Citius, Altius, Fortius” — faster, higher, stronger.

When we watch an overcome athlete, who’s devoted his or her whole life to training, take the podium and stand tearfully before a rising flag, it is easy to recognize the many exceptional benefits to participating in sports. But there is also a darker side of the spectrum that shouldn’t be ignored. The physical strain athletes undergo is well-documented and commonly discussed. Yet what about the mental struggles athletes face, not just at the Olympic level but at all levels?

In the past couple months, there have been many articles reporting that brain ailments in U.S. soldiers have been found to be similar to those found in athletes. The neurodegeneration associated with these injuries correlate heavily with mental health symptoms. For example, the trauma undergone in head injuries can actually alter the brain, leaving many of those injured to experience symptoms of PTSD. As one New York Times article on traumatic brain injury stated:

“There is mounting evidence that traumatic brain injury can affect athletes and soldiers on more than just a physical level. The mental health effects of traumatic brain injury and chronic traumatic encephalopathy are just as debilitating: depression, suicidal ideation, an inability to focus and other issues manifest at every level of injury.”

There is now reason to believe that there are many unaccounted for or “hidden” head injuries in both athletes and soldiers. This is concerning on many levels. A University of Rochester Medical Center study found that, “Even when brain injury is so subtle that it can only be detected by an ultra-sensitive imaging test, the injury might predispose soldiers in combat to post-traumatic stress disorder.”

If ignored or undetected, many athletes may face increased mental health risks without getting the help they need.

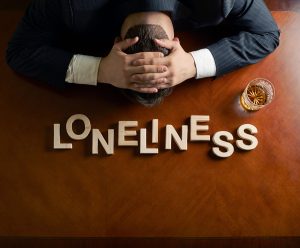

Physical strains endured by athletes are common and considerable. Yet, psychological strain comes not just from bodily injury, but can also rise from the immense pressures of competing, and ultimately the grief of parting with the sport you love. After retiring, athletes may experience a sense of loss. They may lose touch with their identity and purpose. They often face new financial pressures or struggle in their search for a new career. Many athletes are used to experiencing life as part of a team. On their own, they may feel disconnected. After years of build up, praise, and applause, athletes face an unfamiliar and unknown future.

NFL player Brandon Marshall recently opened up publicly about his own psychological struggles and the importance of removing stigmas about mental illness in sports. He wrote in his May 5 op-ed in the Chicago Sun-Times:

“As athletes, we go through life getting praised and worshipped and making a lot of money. Our worlds and everything in them — spouses, kids, family, religion and friends — revolve around us. We create a world where our sport is our life and makes us who we are. When the game is taken away from us or when we stop playing, the shock of not hearing the praise or receiving the big bucks often turns out to be devastating.”

Whether it is feelings of loneliness or isolation or symptoms of PTSD, the struggles athletes face when their career comes to a close can leave them not knowing where to turn for help. At this point, athletes may start to listen to a destructive inner coach, what my father, psychologist and author Dr. Robert Firestone and I have come to refer to as the “critical inner voice.” This internal enemy preys on any vulnerability or perceived weakness, telling us that we are nothing, that we are different, that we are less than, undeserving, or alone. When athletes start to feel separated from the world, they may start to listen to and increasingly believe the commentary of this cruel inner critic. This process may exacerbate their feelings of seclusion, depression, or grief. When a person experiences these symptoms and fails to seek the help they need, tragedy can result.

This makes it all the more necessary for us to remove the negative connotations associated with mental health struggles. The recent suicide of famous former San Diego Charger Junior Seau is part of what prompted Brandon Marshall to speak out about de-stigmatizing mental illness in the sports world. In his op-ed, he described how the directive to “be strong” and keep problems to oneself has early roots for young men in the sports world. “We are teaching our boys not to show weakness or share any feelings or emotions, other than to be strong and tough,” wrote Marshall.

The American Psychiatric Association has noted the dangers of the assumption that athletes should be mentally healthy or the false notion that “being strong” means handling things on your own. Hoping to increase awareness and remove the stigma surrounding the mental health of athletes, the organization published an article listing the following facts:

- First, mental illness is very likely as common in athletes as in the general population.

- Second, it is not a sign of weakness and should be taken as seriously as a physical injury.

- Third, getting help will most likely, improve, not damage one’s self-confidence.

- Lastly, the American Psychiatric Association asks people to acknowledge that sports subject a person to a unique set of challenges and circumstances that can make a person vulnerable to feelings of depression or anxiety.

One of the most significant things we can do when it comes to the mental health of athletes is to remove the stigmas associated with mental illness and enforce the message that help is available. Each person has a right to find the treatment that works for them. Friends, teammates, and family members can offer support by looking for warning signs, paying attention, noticing, and taking seriously signs that the people we love are starting to struggle. Athletes should not be assumed or expected to be machines, especially where their emotions are concerned. In addition to trainers, coaches, and physical therapists, they should be offered psychological support when necessary during their career as well as after retirement.

Contrary to what we are often told, “handling” a problem does not mean holding it inside and keeping it to ourselves. Seeking out mental health assistance is a strong, brave, and proactive decision. Treating a psychological ailment should be given as much importance as treating a physical injury. Athletes inspire us in so many ways. By standing up to the stigma and getting the help they need and deserve, they can become champions of mental health and inspire us with more than just their physical strength.

If you or someone you know is in crisis or in need of immediate help, call 1-800-273-TALK (8255). This is a free hotline available 24 hours a day to anyone in emotional distress or suicidal crisis.

International readers can click here for a list of helplines and crisis centers around the world.

To see upcoming webinars with Dr. Lisa Firestone, click here.

Tags: athletes, head injury, mental health, Suicide, suicide prevention

I read your article in Psychology Today. To make this short, I participated in therapy quite a few times but the same negative result would take over. I was homeless, I can’t believe I told you that, I have only told two other people, for over a year. i get the confidence of others and I self destruct.

Your article on Day Dreaming and the inner voice hit to home more than all the therapy sessions combined. I ask you to please get back to me.

Thank You,

John